Buyer beware: this session is NOT a tool playground.

This afternoon... we think!

Columbia ice strike

- Size: 1200 m2

- Speed: 477 mpg (relative to vehicle)

Certified as “safe” by the CRATER micro-meteorite model.

- A experiment in CRATER’s DB:

- Size: 3cm3

- Speed: under 100 mpg

Columbia, and crew, dies on re-entry

- Lesson: conclusions should come with a “certification envelope”

- If new tests outside of the envelope of the training set then raise an alert

- Knowledge is not universal, laying around like diamonds

- WRONG: Mind is a passive system that gathers its contents from its environment and, through the act of knowing, produces a copy of the order of reality

- Rather, in the act of knowing, it is the human mind that actively gives meaning and order to that reality to which it is responding - We see, we react, then we know

e.g. Explanation

- When explaining something, one size does not fit all. Explanations need to be tailored to the knowledge and goals of the audience.

e.g. Kelly's personel construct theory:

- humans reason about the difference between our constructs rather than the constructs themselves

- Kelly, George (1991) [first publsihed 1955]. The psychology of personal constructs. London; New York: Routledge in association with the Centre for Personal Construct Psychology. ISBN 0415037999. OCLC 21760190.

Roger Shank: people don't think, they remember

- Reasoning = reflecting over one's own library of exemplars of past events

- Learning = finding good exemplars

Note that most data sets contain such exemplars:

- A "well-supported" model is built from N examples, using multiple examples fron N to support different parts of the model

- That is, the N examples contain many repeated effects (and we try to avoid modeling the rare, one-off anomalous effects)

- So any data set that supports a model can be condensed by removing the repeats.

E.g. Reverse nearest neighbors

- Everyone point to their nearest neighbor

- Count how many times someone is pointing to you

- That is your reverse nearest neighbor score

- Sort rows by ther rnn score, print only the highest scroring ones

e.g.786 examples in diabtetes.arff. If we just show the ones with rnn>= 2 then:

#n, /class, rnn, :pedi, :mass, :insu, :skin, :preg, :pres, :age, :plas

#====, =====, =====, =====, =====, =====, =====, =====, =====, =====

# -, -, 100, 98, 95, 89, 84, 72, 46, 0

24, tested_negative, 2, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1 <== 24 repeats

1, tested_negative, 2, 3, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1

%-------------------------------------------------------------------------------

1, tested_positive, 2, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1

1, tested_positive, 2, 1, 1, 1, 1, 3, 1, 2, 1

1, tested_positive, 2, 1, 3, 1, 1, 3, 2, 1, 3

1, tested_positive, 2, 1, 3, 1, 3, 1, 2, 1, 3

1, tested_positive, 2, 1, 3, 2, 3, 1, 1, 1, 3

2, tested_negative, 3, 3, 3, 2, 3, 1, 2, 2, 3

1, tested_positive, 3, 3, 1, 1, 1, 3, 2, 2, 3

1, tested_positive, 3, 3, 3, 2, 3, 1, 2, 1, 3

1, tested_negative, 4, 1, 1, 2, 1, 1, 1, 1, 3

1, tested_negative, 4, 3, 1, 2, 3, 1, 1, 1, 1

1, tested_positive, 4, 1, 3, 2, 3, 3, 2, 2, 3

1, tested_positive, 6, 3, 3, 2, 1, 3, 2, 2, 3

1, tested_positive, 7, 3, 3, 2, 3, 1, 2, 1, 3

1, tested_positive, 12, 3, 3, 2, 3, 3, 2, 2, 3

1, tested_positive, 18, 3, 3, 2, 3, 3, 2, 2, 3

Note, in the above, the numbers have been binned into a small number of groups; e.g. age has 2 groups and preg has 3. why? see below.

BTW, there are many other ways to find these centroids:

- cluster, then for each cluster:

- take center of each cluster

- take the N most remote points in the cluster

- take the N random points in the cluster

- decision tree learning; then for each leaf:

- take center of each leaf

- take the N most remote points in the leaf

- take the N random points in the leaf

- see also, the (very cool) literature on prototype selection; a.k.a. finding exemplars.

- One example is a point is space

- e.g. a=1,b=2,c=3

- Rules are volumes in space

- e.g. a < 1, b< 2 (and c equals anything)

- So, to generalize

- Combine points into bins (discretiation)

- find epsilon ;

- e.g. something less than what the business users can control

- e.g. some small fraction of the standard deviation

- Cohen is a heuristic for detecting trivially small differences. Trivial if less than cohen*sd different

- Cohen=(0.2,0.5,0.8) = small, medium, large

- But this is somewhat contraversial

- Divide data into at least bins of size epsilon

- find enough

- e.g. sqrt(N)

- divide numbers into bins bigger than enough

The following code applies epsilon and enough to split the data in nums.all (see the third and fourth if statement). The other if statements handle some weird end cases.

function binsGrow(t,nums,b,

epsilon,enough,r,ranks,j,most,val) {

epsilon = nums.sd * b.cohen

enough = length( t.rows )^b.m

most = last(nums.all)

has(b.ranks, 1, "Num")

r = 1

for(j=1; j<=t.n; j++) {

val = nums.all[j]

NumAdd( b.ranks[r], val )

if ( most - val > epsilon )

if( t.n - j > enough )

if( b.ranks[r].n > enough )

if( b.ranks[r].hi - b.ranks[r].lo > epsilon )

has( b.ranks, ++r, "Num" ) }

return r

}Don't split things unless those splits decrease confusion.

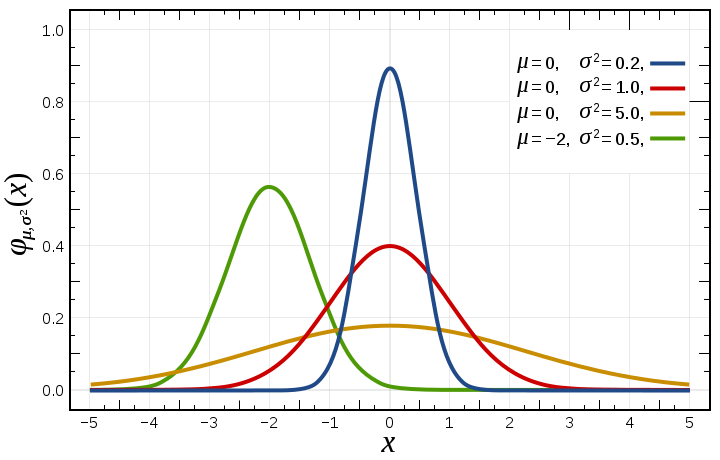

- For numbers and symbols, confusion is called variance and entropy.

First, variance:

- A class for collecting means and standard deviations

- incremental computation of var, mean

- detecting different distributions - see these lines for the core test

Second, entropy

- entropy = number of bits needed to encode a signal

- eg. yes,yes, yes, no,no = (3/5, 2/5)

- ent = -1* sum p*log2(p) = -1*(2/5*log2(2/5) + 3/5*log2(3/5) = 0.97

If divisions of data do not decreases varaince/entropy, then that is a bad division:

- e.g. 10 orranges, 5 green apples, 1 watermelon

- before division: ent = -1*(10/16*log2(10/16) + 5/16*log2(5/16) + 1/16*log2(1/16)) = 1.6

- considering dividing on color= orange and color=green

- after division there are 10,6 orange and green things

- ent= -1*(10/16*log2(10/16) + 6/16*log2(6/16)) = 0.95

- code

Example. The following code is run as a post-processor to binsGrow (shown above). Bins that should be combined get the same rank;

Aside: this cose uses expectedValue

- If there are obs of "x1" and "x2" seen in "n1" and "n2" examples then

- n=n1+n2

- Expected value = E = n1/n * x1 + n2/n * x2

- e.g. see the tmp line, below:

Which the following code uses to recursively split the bins generated above:

function binsCuts(lo,hi,ranks,b4,r,

j,best,n,mid,x,y,xx,yy,tmp,cut) {

best = b4.sd

if (lo < hi)

for(mid=lo+1; mid<=hi; mid++) {

xpect(x, lo, mid, ranks)

xpect(y, mid+1, hi, ranks)

tmp = x.n/b4.n*x.sd + y.n/b4.n*y.sd #<== for symbols, change .sd to .ent

if (tmp < best)

if ( diff(x,y) ) { #<== explained below

cut = mid

best = tmp

copy(x,xx)

copy(y,yy)

}}

if (cut) {

r = binsCuts(lo, cut, ranks, xx, r) + 1 # <== recursive call

r = binsCuts(cut+1, hi, ranks, yy, r)

} else

for(j=lo; j<=hi; j++)

ranks[j].rank= r

return r

}Aside: this code needs two helper function

function Xpect(i) {

new(i);

i.n = i.mu = i.sd = 0

}

function xpect(x,lo,hi,ranks, j,n1) {

Xpect(x)

for(j=lo; j<=hi; j++)

x.n += ranks[j].n

for(j=lo; j<=hi; j++) {

n1 = ranks[j].n

x.mu += n1 / x.n * ranks[j].mu

x.sd += n1 / x.n * ranks[j].sd

}}Use statistical theory to block spurious splits

- See the diff call, made above.

Which means we need to know some stats:

- Significance tests (e.g. the t-test) check if to distributions are different by more than random chance

- Effect size tests (e.g. hedges) comment on the size of the difference

- We use both

function diff(x,y, s) {

Stats(s)

return hedges(x,y,s) && ttest(x,y,s)

}For this to work, we need fast ways to incrementally collect mu and standard deviation:

In the following, we use assue x,y can report their mean and standard deviation and sample size as e.g.

x.n, x.mu, x,sd.

The Hedges effect size test using magic numbers from this study. If checks of the difference in the mean divided by the standard deviation is bigger than some magic number (0.38)

function hedges(x,y,s, nom,denom,sp,g,c) {

nom = (x.n - 1)*x.sd^2 + (y.n - 1)*y.sd^2

denom = (x.n - 1) + (y.n - 1)

sp = sqrt( nom / denom )

g = abs(x.mu - y.mu) / sp

c = 1 - 3.0 / (4*(x.n + y.n - 2) - 1)

return g * c > 0.38 # from https://goo.gl/w62iIL

}The t-test significance test is very similar. It uses ttest to look up a magic threshold value. For details see here.

function ttest(x,y,s, t,a,b,df,c) {

# debugged using https://goo.gl/CRl1Bz

t = (x.mu - y.mu) / sqrt(max(10^-64,

x.sd^2/x.n + y.sd^2/y.n ))

a = x.sd^2/x.n

b = y.sd^2/y.n

df = (a + b)^2 / (10^-64 + a^2/(x.n-1) + b^2/(y.n - 1))

c = ttest1(s, int( df + 0.5 ), s.conf)

return abs(t) > c

}The above methods:

- divide many continuous distributions into a handful of bins

- select for a handful of rows

- allow us to find a handful of most useful columns

- and that reduced space works just as well for data mining as the original space

BTW, once we know how to do exemplars:

- big data moves to little data

- big data is useful for initial data collection

- little data is where all the subsequent inference happens

- The secret of big data is little data

- we can ship models with a certification envelope; i.e. the core examples from which we defined a model

- ring an alarm bell if new data not in the certification envelope

- no more crashing columbia space shuttles.

maths that matters my Spiel would be cognitive. that stats are "m'eh" but the real game is showing decision makers things that let them do things. so informative "visualizations" that highligtht the deltas between things (Kelly's personnel construct theory: folks dont know "things", what they really know are the minimal differences between things) . which leads to the mathematics of diversity (entropy, variance) and how to distinguish between things (bootstrapping, effectSize) and how to apply that theory of differences to data mining (clustering, discretization, recursive tree learning). the final cherry on this cake would be scott-knot stuff seen at icse recently where results are chunked up into BIG groups and we no longer focus on micro deltas but on BIG MOFO DIFFERENCES. so not sure if that is an REU thing or a lecture for my foundations of software science thing in the fall your call. happy to help. happy to not. what ya need? Cognitive maths. Maths that fuels human decision making:

- explaination is task-depnedent: supervised learning rules (different atsks, different learning)

- instance-based reasoning: don't think, rememoer over a small library of examplars

- Don't sweat the small stuff: effect size, scott-knott

- Maths of n-dimensional sphere: low-dimensional or not at all (+)

- Kelly's peresonnel constract theory: dont show what is, show what is different

- Minimize confusion: reduce expected value of variance or entropy

(+) note: cool if we are human intelligence. May not hold for super-human intelligence.