VACUUM is an essential command in PostgreSQL its goal is to clean out dead rows, which are not needed by anyone anymore. The idea is to reuse space inside a table later as new data comes in. The important thing is: The purpose of VACUUM is to reuse space inside a table – this does not necessarily imply that a relation will shrink. Also: Keep in mind that VACUUM can only clean out dead rows, if they are not need anymore by some other transaction running on your PostgreSQL server.

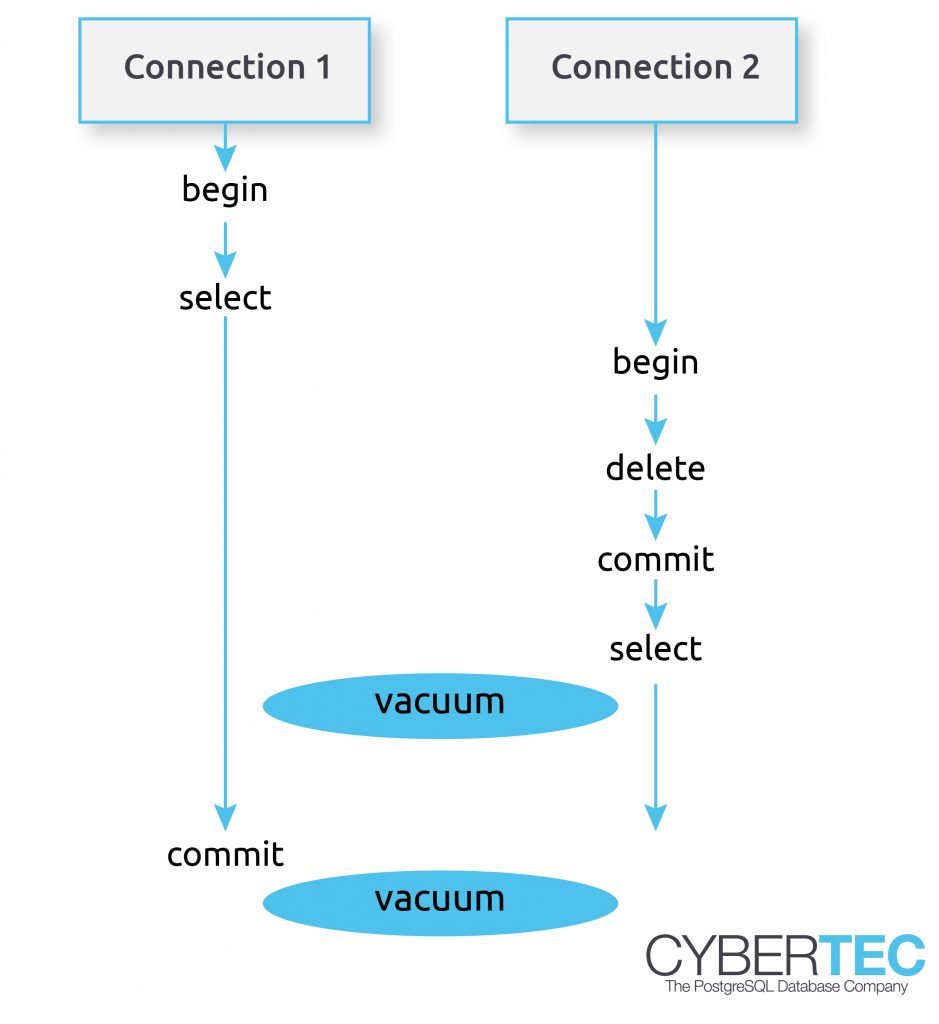

Consider the following image:

As you can see we have two connections here. The first connection on the left side is running a lengthy SELECT statement. Now keep in mind: An SQL statement will basically “freeze” its view of the data. Within an SQL statement the world does not “change” – the query will always see the same set of data regardless of changes made concurrently. That is really really important to understand.

Let us take a look at the second transaction. It will delete some data and commit. The question that naturally arises is: When can PostgreSQL really delete this row from disk? DELETE itself cannot really clean the row from disk because there might still be a ROLLBACK instead of a COMMIT. In other words a rows must not be deleted on DELETE. PostgreSQL can only mark it as dead for the current transaction. As you can see other transactions might still be able to see those deleted rows. However, even COMMIT does not have the right to really clean out the row. Remember: The transaction on the left side can still see the dead row because the SELECT statement does not change its snapshot while it is running. COMMIT is therefore too early to clean out the row.

This is when VACUUM enters the scenario. VACUUM is here to clean rows, which cannot be seen by any other transaction anymore. In my image there are two VACUUM operations going on. The first one cannot clean the dead row yet because it is still seen by the left transaction. However, the second VACUUM can clean this row because it is not used by the reading transaction anymore.

On a single server the situation is therefore pretty clear. VACUUM can clean out rows, which are not seen anymore.

What happens in a master / slave scenario? The situation is slightly more complicated because how can the master know that some strange transaction is going on one of the slaves?

Here is an image showing a typical scenario:

In this case a SELECT statement on the replica is running for a couple of minutes. In the meantime a change is made on the master (UPDATE, DELETE, etc.). This is still no problem. Remember: DELETE does not really delete the row – it simply marks it as dead but it is still visible to other transactions, which are allowed to see the “dead” row. The situation becomes critical if a VACUUM on the master is allowed to really delete row from disk. VACUUM is allowed to do that because it has no idea that somebody on a slave is still going to need the row. The result is a replication conflict. By default a replication conflict is resolved after 30 seconds:

`ERROR: canceling statement due to conflict with recovery``Detail: User query might have needed to see row versions that must be removed`

If you have ever seen a message like that – this is exactly the kind of problem we are talking about here.

To solve this kind of problem, we can teach the slave to periodically inform the master about the oldest transaction running on the slave. If the master knows about old transactions on the slave, it can make VACUUM keep rows until the slaves are done. This is exactly what hot_standby_feedback does. It prevents rows from being deleted too early from a slave’s point of view. The idea is to inform the master about the oldest transaction ID on the slave so that VACUUM can delay its cleanup action for certain rows.

The benefit is obvious: hot_standby_feedback will dramatically reduce the number of replication conflicts. However, there are also downsides: Remember, VACUUM will delay its cleanup operations. If the slave never terminates a query, it can lead to table bloat on the master, which can be dangerous in the long run.