(code-preliminaries)=

In this chapter, you'll find out about how to get the basic tools you need to code set up on your own computer. While you don't need to know all of this if you're planning on using the book interactively via 'Google Colab' (to run code examples), you will find it helpful to read through this chapter anyway.

Almost all of the code you'll see can be run on all three of the major operating systems: Windows, MacOS, and Linux, as well as in free online notebooks provided by Google (this service is called Google Colab).

If you haven't yet decided which operating system to use, this book recommends either Linux or MacOS because, in a very small number of cases, you'll find it easier to run the most advanced code on them rather than on Windows. Don't panic if you have Windows already though—most things will work just fine and it tends to be power users who run into this problem. (If you're not familiar with Linux, it's a free operating system that is also widely used for cloud services and, while it used to have a reputation as being fearsomely difficult for beginners, some modern Linux distributions, such as Ubuntu, are pretty user-friendly.)

If you have Windows and you want to use Linux or Mac but don't want to shell out for a new computer, there are a couple of options. One is to use the Windows Subsystem for Linux. It's essentially a Linux operating system that installs alongside and integrates with your existing Windows operating system. This allows you to run code as if you were using Linux. You can get WSL for free from Microsoft (the fact that Microsoft has included this feature speaks to the demand for it). Another option is to use Github Codespaces, which gives cheap (but not free) access to a pre-built Linux machine in the cloud. A further option is Gitpod, which is like Codespaces but has a generous free tier.

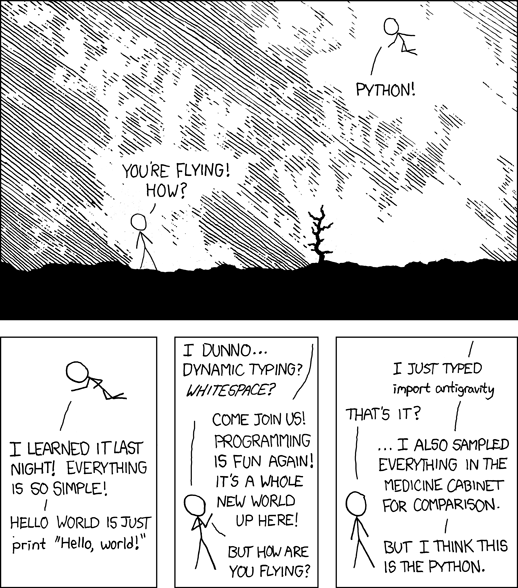

This book uses Python, which is usually ranked as the first or second most popular programming language in the world and, just as importantly, it's also one of the easiest to learn. It's a general purpose language, which means it can perform a wide range of tasks. This combination of features is why people say Python has a low floor and a high ceiling. It's also very versatile; the joke goes that Python is the 2nd best language at everything, and there's some truth to that (although Python is 1st best at some tasks, like machine learning). But a language that covers such a lot of ground is also very useful; and Python is widely used across industry, academia, and the public sector, and is often taught in school computer science classes too. Python is the main 'dynamic' language used at Google and the most demanded language in jobs for Apple. It is used for everything from computer games to websites, data science to software applications: it's even being used to help fly a helicopter on Mars. As an economist, you will know that this means Python benefits from strong positive network externalities. As such, learning Python has a lot of value and, once you have, learning more specialised languages like C++ or R is much easier; many of the basic programming concepts you'll see in this book are useful in almost any programming language. One other benefit of Python if you plan to do any work on the cloud is that it is extremely well supported.

Python, from xkcd.

Different languages have different strengths and weaknesses. Python and Julia are so-called high-level languages that are easier to write code in. C++ and Fortran are more low-level languages and much more fussy and labour-intensive to write code in; but, once the code is written (and 'compiled'), it runs fast.

Another big difference between languages is the extent to which users have created software that extends the base functionality of the language. The ecosystem of other users, and what they're using the language for, is really important for determining how useful a language is. For example, Python and R have vibrant data science communities producing extensions (called libraries or packages) that are what really make those languages so useful for data science (far more than the base functionality of either).

Programming languages come in versions, which can be quite different, and some of the most important functionality of programming languages is provided by add-ons called packages or libraries, which themselves have versions. To make matters worse, not all versions of packages and languages will work together, and the combinations that work may depend on your operating system (Windows, Mac, etc)!

The combination of the language and its version (eg Python 3.8), the packages and their versions (eg numpy 1.19), and the operating system the code is being run on (eg MacOS Catalina) is called the computational environment. This book is written with Python 3.8.

To programme, you will need two things on your computer:

-

an installation of the programming language (also known as the "interpreter"), for example Python 3.8

-

a way to write and run your code, using an integrated development environment (IDE), for example Visual Studio Code

The Anaconda distribution of Python, which this book recommends, is available on all major operating systems. To install it, follow the instructions below or watch the video.

<iframe width="700" height="394" src="https://www.youtube.com/embed/ZWQwGR5ppnk" title="YouTube video player" frameborder="0" allow="accelerometer; autoplay; clipboard-write; encrypted-media; gyroscope; picture-in-picture" allowfullscreen></iframe>How to install Python using the Anaconda distribution of Python

Download the individual edition of the Anaconda distribution of Python for your operating system and install it (on Anaconda's website, this is currently found under Products -> Individual Edition). This will provide you with a Python installation and a host of the most useful libraries. If you get stuck, there are more detailed instructions available for installing the Anaconda distribution of Python on Windows, on Mac, and on Linux.

You can confirm that you've set up Anaconda correctly by following the verify installation instructions on the Anaconda website. If you're using Windows, you can check if Anaconda has installed properly by opening the 'Anaconda prompt' (a special text-based way to issue commands to your computer) and type where python. You should see a path rendered as text in the prompt that includes "Anaconda3", for example something like C:\Users\<your-username>\Anaconda3\.... On Mac and Linux you may need to run conda init on your command line to activate your Anaconda Python environment (Mac and Linux usually come with, typically, old versions of Python pre-installed). You can check you've got the right Python with which python, which should result in a message back saying /Users/<your-username>/opt/anaconda3/bin/python.

An integrated development environment is a software application that provides a few tools to make coding easier. The most important of these is a way to write the code itself! IDEs are not the only way to programme, but they are perhaps the most useful. If you have used Stata or Matlab, you may not have realised it, but these package up the language and the IDE together. But they are separate things: the language is a way of processing your instructions, the IDE is where you write those instructions.

Here are some of the useful features an IDE might have:

-

a way to run your code interactively (line-by-line) or all at once

-

a way to debug (look for errors) in your code

-

a quick way to access helpful information about commonly used software packages

-

automatic code formatting, so that your code follows best practice guidelines

-

auto-completion of your code

-

automatic code checking for basic errors

-

colouring your brackets in pairs so you can keep track of the logical order of execution of your code!

People have strong feelings about which IDE they prefer. This book strongly recommends Visual Studio Code, a free and open source IDE from Microsoft that is available on all major operating systems. Just like Python itself, Visual Studio can be extended with packages, and it is those packages, called extensions in this case, that make it so useful. As well as Python, Visual Studio Code supports a ton of other languages.

Visual Studio Code supports coding in both scripts and Jupyter Notebooks. While scripts mostly contain code (and have file extension .py), notebooks can contain text and code in different blocks called cells. 'Jupyter Notebooks' have the file extension '.ipynb'. The name, 'Jupyter', is a reference to the three original languages supported by Jupyter, which are Julia, Python, and R, and to Galileo's notebooks recording the discovery of the moons of Jupiter. Jupyter notebooks now support a vast number of languages beyond the original three, including Ruby, Haskell, Go, Scala, Octave, Java, and more. There'll be more about the difference between scripts and notebooks later on in the book.

Another IDE that you might find useful from time to time is Jupyter Lab, which runs in a browser window; for now, we'll keep our focus on Visual Studio Code.

Download and install Visual Studio Code. If you need some help, the video below will walk you through downloading and installing Visual Studio Code, and then using it to run Python code in both scripts and in notebooks. We'll go through these instructions in detail in the rest of this chapter. As an alternative to the instructions or video below, Microsoft also has a very short tutorial on setting it up (ignore the bits about debugging and installing packages for now).

<iframe width="700" height="394" src="https://www.youtube.com/embed/1kKTYsQdaPw" title="YouTube video player" frameborder="0" allow="accelerometer; autoplay; clipboard-write; encrypted-media; gyroscope; picture-in-picture" allowfullscreen></iframe>How to install Visual Studio Code and use it to run Python code

Once you have Visual Studio Code installed and opened, navigate to the 'extensions' tab on the left hand side vertical bar of icons (it's the one that looks like 4 squares). You'll need to install the Python extension for VS Code, which you can search for by using the text box within VS Code's extensions panel.

The figure above shows the typical layout of Visual Studio Code. The long vertical panel on the far left-hand side changes what is seen in panels 1 and 2; it currently has the file explorer selected. Let's run through the numbered parts of the figure.

- When the explorer option is selected from the icons to the left of 1 and 2, the contents of the folder that's currently open are shown in 1.

- This is an outline of the key parts of the file that is open in 3.

- This is just a fancy text editor. In the figure above, it's showing a Python script (a file that contains code and has a name that ends in

.py). Selecting code and pressing Shift + Enter ('Enter' is labelled as 'Return' on some keyboards) will execute that code in 5. - This is the command line, a place where you can type in commands that your computer will then execute. If you want to try a command, type

date(Mac/Linux) ordate /t(Windows). - This is the interactive Python window, which is where code and code outputs appear after you select and execute them from a script (see 3). It shows the code that you executed and any outputs from that execution—in the screenshot shown, the code has created a plot. The name and version of Python you're using appear at the top of the interactive window.

Note that there is lots of useful information arrayed right at the bottom of the window in the blue bar, including the version of Python currently being used by VS Code.

If you have installed the Anaconda distribution of Python, Visual Studio Code, and the Python extension for VS Code, then you are ready to run your first script!

Now you will create and run your first code. If you get stuck, there's a more in-depth tutorial over at the VS Code documentation.

Create a new folder for your work (perhaps named 'codingforeconomists', no white space), open that folder with Visual Studio Code and create a new file, naming it hello_world.py. The file extension, .py, is very important as it implicitly tells Visual Studio Code that this is a Python script. In the Visual Studio Code editor, add a single line to the file:

print('Hello World!')Save the file.

If you named this file with the extension .py then VS Code will recognise that it is Python code and you should see the name and version of Python pop up in the blue bar at the bottom of your VS Code window. Make sure that the version of Python displayed here is the Anaconda version that you just installed rather than one that comes built-in with your operating system (this is particularly an issue on Mac). If you have a fresh install of Anaconda's distribution of Python, you'll probably see something like Python 3.8 64-bit ('base': conda). To change which Python version your code uses, click on the version shown in the blue bar and select the version you want. If you've just changed Python version, it can be a good idea to restart VS Code so that all the versions of Python on your system are picked up by it.

When you press save, you may get messages about installing extra packages or making Pylance your default language server; just go with VS Code's suggestions here, except the one about the terminal and conda, which you can say no to.

Alright, shall we actually run some code? Select/highlight the print('Hello world!') text you typed in the file and right-click to bring up some options including 'Run Selection/Line in Terminal' and `Run Selection/Line in Interactive Window'. Because VS Code is a richly featured IDE, there are lots of options for how to run the file. Let's try both of the main ways: via the interactive window and using the "terminal" (more on what that is later).

The interactive window is a convenient and flexible way to run code that you have open in a script or that you type directly into the interactive window code box. The interactive window will 'remember' any variables that have been assigned (for examples, code statements like x = 5), whether they came from running some lines in your script or from you typing them in directly. Working with the interactive window will feel familiar to anyone who has used Stata, Matlab, or R, and is much more suited to the way economists tend to work because it doesn't require you to write the whole script, start to finish, ahead of time. Instead, you can jam, changing code as you go, (re-)running it line by line.

To run the code in an interactive window, right-click and select 'Run Selection/Line in Interactive Window'. This should cause a new 'interactive' panel to appear within Visual Studio Code, and only the selected line will execute within it. At this point, you may see a message about Visual Studio Code's default behaviour when you press Shift + Enter; for this book, it's good to have Shift + Enter default to running a line in the interactive window. The box below has instructions for how to ensure this always happens.

:class: dropdown

Open up Visual Studio Code and go to settings (click on the cog in the bottom left-hand corner, then click settings).

Type 'python send' into the search box. Depending on your configuration and Visual Studio Code version, you will either see 'Python › Data Science: Send Selection To Interactive Window' or 'Jupyter: Send Selection To Interactive Window'. Make sure that there is a tick in the box.

This will ensure that when you hit shift+enter on code scripts, it will execute your code in Visual Studio's interactive window (starting a new window if necessary).

Let's make more use of the interactive window. At the bottom of it, there is a box that says 'Type code here and press shift-enter to run'. Go ahead and type print('Hello World!') directly in there to achieve the same effect as running the line from your script. Also, any variables you run in the interactive window (from your script or directly by entering them in the box) will persist.

To see how variables persist, type hello_string = 'Hello World!' into the interactive window's code entry box and hit shift-enter. If you now type hello_string and hit shift+enter, you will see the contents of the variable you just created. You can also click the grid symbol at the top of the interactive window (between the stop symbol and the save file symbol); this is the variable explorer and will pop open a panel showing all of the variables you've created in this interactive session. You should see one called hello_string of type str with a value Hello World!.

This shows the two ways of working with the interactive window--running (segments) from a script, or writing code directly in the entry box.

:class: dropdown

In Visual Studio Code, you can ensure that the interactive window starts in the root directory of your project by setting "Jupyter: Notebook File Root" to `${workspaceFolder}` in the Settings menu. For the integrated command line, change "Terminal › Integrated: Cwd" to `${workspaceFolder}` too.

To run code the other way, in the terminal, right-click and select 'Run Python file in terminal'. This will bring up a new panel (called a terminal) within Visual Studio Code that runs your entire script from top to bottom-and you should see 'Hello World!' pop up! Although we're trying out running code in the terminal, the typical economics workflow would be to work with the interactive window.

Create a new script that, when run, prints "Welcome to coding for economists" and run it in both the terminal and an interactive window.

Packages (also called libraries) are key to extending the functionality of Python. The default installation of Anaconda comes with many (around 250) of the packages you'll need, but it won't be long before you'll need to install some extra ones. There are packages for geoscience, for building websites, for analysing genetic data, and, yes, of course, for economics. Packages are typically not written by the core maintainers of the Python language but by enthusiasts, firms, researchers, academics, all sorts! Because anyone can write packages, they vary widely in their quality and usefulness. There are some that are key for an economics workflow, though, and you'll be seeing them again and again.

<script async src="https://platform.twitter.com/widgets.js" charset="utf-8"></script>Name a more iconic trio, I'll wait. pic.twitter.com/pGaLuUxQ3r

— Vicki Boykis (@vboykis) August 23, 2018

The three Python packages numpy, pandas, and maplotlib, which respectively provide numerical, data analysis, and plotting functionality, are ubiquitous. So many scripts begin by importing all three of them, as in the tweet above!

Python packages don't come built-in (by definition) so you need to install them (just once, like installing any other application), and then import them into your scripts (whenever you use them in a script). When you issue an install command for a specific package, it is automatically downloaded from the internet and installed in the appropriate place on your computer.

To install extra Python packages, you issue install commands to a text-based window called the "terminal".

The terminal is also known as the command line and sometimes the command prompt. It was labelled 4 in the screenshot of Visual Studio Code from earlier in the chapter. The terminal is a text-based way to issue all kinds of commands to your computer (not just Python commands) and knowing a little bit about it is really useful for coding (and more) because managing packages, environments (which we haven't yet discussed), and version control (ditto) can all be done via the terminal. We'll come to these in due course, but for now, a little background on what the terminal is and what it does.

To open up the command line within Visual Studio Code, use the <kbd>⌃</kbd> + <kbd>\`</kbd> keyboard shortcut (Mac) or <kbd>ctrl</kbd> + <kbd>\`</kbd> (Windows/Linux), or click "View > Terminal".

Windows users may find it easiest to use the Anaconda Prompt as their terminal, at least for installing Python packages.

If you want to open up the command line independently of Visual Studio Code, search for "Terminal" on Mac and Linux, and "Anaconda Prompt" on Windows.

Firstly, everything you can do by clicking on icons to launch programmes on your computer, you can also do via the terminal, also known as the command line. For many programmes, a lot of their functionality can be accessed using the command line, and other programmes only have a command line interface (CLI), including some that are used for data science.

The command line interacts with your operating system and is used to create, activate, or change python installations.

Use Visual Studio Code to open a terminal window by clicking Terminal -> New Terminal on the list of commands at the very top of the window. If you have installed the Anaconda distribution of Python, your terminal should look something like this as your 'command prompt':

(base) your-username@your-computer current-directory %on Mac, and the same but with '%' replaced by '$' on linux, and (using the Anaconda Prompt)

(base) C:\Users\YourUsername>on Windows. If you don't see the word (base) at the start of the line, you may need to type conda activate first.

The (base) part is saying that your current Python environment is the base one (later, we'll see how to add others for reproducibility and to isolate projects). Unfortunately, and confusingly, the commands that you can use in the terminal on Mac and Linux, on the one hand, and Windows, on the other, are different but many of the principles are the same.

For now, to at least try out the command line, let's use something that works across all three of the major operating systems. Type python on the command prompt that came up in your new terminal window. You should see information about your installation of Python appear, including the version, followed by a Python prompt that looks like >>>. This is a kind of interactive Python session, in the terminal. It's much less rich than the one available in Visual Studio Code (it can't run scripts line-by-line, for example) but you can try print('Hello World!') and it will run, printing your message. To exit the terminal-based Python session, type exit() to go back to the regular command line.

You can find out more about the terminal in the chapter on {ref}wrkflow-command-line.

To install extra Python packages, there are two options, and both use the command line.

You'll need to have conda "activated" before installing a package in the terminal--if you don't see the name of an environment, eg `(base)`, at the start of your terminal's line, use the `conda activate` command first. On Windows, this is usually the command prompt (available in the integrated Visual Studio Code terminal) or the Anaconda Command Prompt (available in the start menu).

Install packages on the command line by typing

conda install package-nameand hitting return, where package-name might be pandas. This will try to install a version of the package that is already optimised for your type of computer, and will automatically come with any dependencies (packages the package you're installing needs to run). The pre-built packages that are provided by Anaconda are convenient for a host of reasons. Anaconda provide pre-built versions of around 7,500 of the most popular packages (including the statistical programming language R).

However, there are over 330,000 Python packages on PyPI (the Python Package Index) so you may sometimes find one that is not covered by conda install. When there isn't a pre-built Anaconda version of a package available, the next thing to try is

pip install packagenameIn true programming-humour style, pip is a recursive acronym that stands for 'pip install packages'. You can see what packages you have installed by entering conda list into the command line.

Here's a full example of the commands used to install the pandas package into the base environment (you may not need the first one):

your-username@your-computer current-directory % conda activate

(base) your-username@your-computer current-directory % conda install pandasTry installing the **matplotlib**, **pandas**, and **statsmodels** packages using `conda install`.

Install the **skimpy** package. (Hint: `conda install` may not be enough.)

That's it for the preliminaries! Well done if you made this far: starting is the hardest bit. There are some extra bits below for if you're coding on a restricted work computer or you want to add all the bells and whistles to Visual Studio Code, but you can safely skip these if you just want to get on with some coding.

So, if you have:

- ✅ installed Python, using the Anaconda distribution of Python;

- ✅ installed Visual Studio Code, and its Python extension;

- ✅ written and saved 'hello_world.py' with

print('Hello World!')in it; - ✅ run 'hello_world.py' in the Visual Studio Code interactive window; and

- ✅ installed packages in the terminal using both

conda installandpip install, then

you are ready to move on to the next chapter! 🚀

The rest if this chapter contains extras that could be helpful to some people. However, if you just want to get on with some coding or you don't think they apply to you, skip them and move on to the next chapter.

If you're not planning to code at work, or your place of work allows you to install whatever programmes you like, this section won't be relevant to you.

Ideally, you want to have full flexibility over the coding languages, IDEs, and tools that you can install and use. Unfortunately for anyone who wants to code at work, some work computer systems are locked down to the point where programming languages and the tools needed to use them are not able to be installed (often for extremely good reason). Even very big, well-funded organisations can struggle with the problem of providing a good platform for coding, analysis, and data science while also ensuring that the core systems are secure. IT departments faced with this trade-off are increasingly opting to separate out the base environment (where you receive your emails and so on) from the 'developer environment' (the computers that you code on) because it's usually safer to access a less secure computing environment from a more secure computing environment (rather than the other way around). For example, you might use your secure laptop to access a separate data science platform remotely. Although this setup can be frustrating, it can actually enforce lots of good practice too, so it's not all bad—and it does mean you have a chance of accessing more powerful systems with the latest software and hardware.

Organisations that are further along their coding and automation journey will likely provide you with access to cloud computing environments that support Visual Studio Code and Python, and you should speak to your IT department about what's available. However, even if your organisation hasn't invested in coding capabilities to the same extent, but does have locked down IT, there are some options for you!

Let's explore some options for coding platforms 'in a box' that do not require any installation, and can be accessed via the internet. Note that your IT department may still have blocked the URLs of the websites of these services, but you can always make a case for unblocking them until the same capabilities are available in-house.

Google Colab is a great way to start learning and trying out the exercises in this book remotely without having to install anything on your computer. Most pages in this book that have code on are just a click away from launching a Colab notebook—just click the 🚀 at the top of a page with code on and select 'Colab'. Google Colab is fantastic for trying things out, sharing tinkering with others, and generally having a first go at some coding, but it only supports notebooks.

If you need the full power of Visual Studio Code, which supports scripts and notebooks, the easiest way is to use Github Codespaces or Gitpod. Codespaces provides cheap access to a ready-made Visual Studio Code development environment in your browser window. Gitpod is similar, but also has a free tier. Many IT departments will use Github themselves, so you may find your organisation already has a subscription to GitHub (and therefore Codespaces) can use. Another advantage of using a Github subscription is that you can use Github for version control too (if 'version control' is new to you, don't worry—it's just a way of efficiently working with files that have code in).

Finally, if you're just starting to learn and don't need to save any data or code, or use any non-standard packages, you can run a limited instance of JupyterLab (an IDE) in your browser window using JupyterLite. This will be slower than regular Python because all of the computation is done by your browser (eg Google Chrome), as opposed to by your computer directly. And, also because of how this magic is put together, only some packages are available. To use it, head to the JupyterLite website and click on the link that says Try it with JupyterLab!. Once the page loads, select Pyolite Notebook. Note that if you have very high levels of security at your organisation, this website may be blocked from running.

If you're not using Visual Studio Code or you're not ready to delve deeper into its settings, you can safely ignore this section.

Once you've downloaded and installed Visual Studio Code, and installed the Python extension, you'll have enough to get going but VS Code can do a whole lot more with some extra add-ons. You can install these using the extensions tab on the left hand side of VS Code. Here are the ones this book recommends and why:

- Markdown extensions - markdown is a simple text language that is often used to provide READMEs for code repositories. It comes with the file extension .md

- Markdown All in One, to help writing Markdown docs.

- Markdown Preview Enhanced, to view rendered markdown as you type it (right click and select 'Open Preview...').

- Coding extensions

- Jupyter provides support for Jupyter Notebooks

- indent-rainbow, gives different levels of indentation different colours for ease of reading.

- Path Intellisense, autocompletes filenames in code.

- Version control

- Git History, view and search your git log along and show a graph of git commits with details.

- GitLens, helps to visualise code authorship at a glance via 'Git blame' annotations, navigate and explore Git repositories, and more.

- Code Spell Checker, does exactly what it says, really useful for avoiding mangled variable name errors. If you need it to use, for example, 'British English', change the 'C Spell: Language' text from 'en' to 'en-GB' in VS Code's settings. Other languages are available as separate extensions.

- General

- Rainbow CSV, uses colour to make plain old CSV files much more readable in VS Code.

- vscode-icons, intelligent icons for your files as seen in the VS Code file explorer, eg a folder called data gets an icon showing a disc drive superimposed onto a folder.

- polacode, take pictures of code snippets to share on social media

- Excel viewer, does what it says

- Selection Word Count, calculates and displays the word count of a document and, when there is a selection, the word count of a selection (both are shown in the status bar)

- LiveShare, to collaborate on code with someone else in real-time

- LaTeX - it's a bit of surprise, but VS Code is one of the best LaTeX editors out there. You will need LaTeX installed already though and initial setup of a compilation 'recipe' is a bit fiddly (though, once it works, it's dreamy).

- LaTeX Workshop, provides core features for LaTeX typesetting with Visual Studio Code.

- LaTeX Preview, both in-line and side-by-side previews of LaTeX code. A really fantastic extension.

There are some extensions that most people won't need but which experienced coders may find useful:

- Github Pull Request — allows you to review and manage GitHub pull requests and issues in Visual Studio Code

- Remote development — allows you to open any folder in: a container, a remote machine, or the Windows Subsystem for Linux (WSL)

- Remote - WSL — run VS Code in the Windows Subsystem for Linux

- Remote - SSH — run VS Code over an SSH connection, eg in the cloud

- Remote - Container — run VS Code in a Docker container

- Python Docstring Generator — automatically generates part of the documentation for your Python functions

- Docker - makes it easy to build, manage, and deploy Docker containers from Visual Studio Code

As well as adding extra extensions, you can customise the default settings of VS Code. As mentioned before, you'll probably want to change the jupyter.sendSelectionToInteractiveWindow setting to True. The easiest way to do this is to go to Settings (the cog icon) and type in 'Jupyter: Send Selection', and you should see a tick box come up; make sure it's ticked. Another useful one for coding is to change the 'Editor: Render Whitespace' setting, aka editor.renderWhitespace from 'selection' to 'boundary'. This will now show any boundary whitespace, or more than one instance of whitespace contiguously, as a grey dot. This might seem odd but it's really useful because the wrong amount of whitespace can create problems with code.