The goal of this project is to program a Quadcopter to identify a target and follow it.

1. Analyze a stream of images coming from our front-facing camera on the drone 2. Classify each pixel using a Fully Convolutional Neural Network 3. Locate our target(the 'hero'/lady in red) in the pixels 4. Follow the target with the Quadcopter

We operate the quadcopter through QuadSim (ran locally).

The code for the segmentation network can be found at model_training.ipynb

This README is broken into the following sections: Model Development, and Future Enhancements.

Although I collected some of my own data, I opted to start with the images provided to us by Udacity and see what accuracy I could get. Those can be found here, here, and here.

Because we're challenged with the task of not just understanding what is in an image, but we need to figure out where the object is in the image, we're going to be using a network full of convolutional layers (FCN).

At first glance, we might think to just put many full-scaled convolutional layers one after another. This is good intuition, but we soon find this generates too many parameters, and becomes computationally very expensive.

Instead, we'll use a method of first extracting important features through encoding, then upsample into an output image in decoding, finally assigning each pixel to one of the classes.

Of course, every method has its disadvantages, and we'll lose some specific pixels during downsampling, and interpolate some during upsampling, but we'll also find out that this loss is negligible, and worth the increase in speed of computation due to decreased dimensionality.

I decided to start with the symmetrical, 5 layer model architecture, like the one shown in the lecture. From what I've read, especially from recent research on networks like ResNet, more layers are usually better, as long as they are not plain layers. But also, as networks become deeper, they take longer and longer to train. I figured 5 layers was a fair place to start.

I also noticed GoogleNet and Resnet had 64, 128, and 256 layers of depth. This is the number of kernels I opted for in the encoder, 1x1 convolution, and decoder. So the network, from a depth point of view, is structured in the following manner: Input > 64 > 128 > 256 > 128 > 64 > Output

The network architecture can be seen here:

We know our original 256x256x3 images have been resized to 160x160x3 with data_iterator.py. This gives our input layer size input = 160,160,3.

Because we've used a 1x1 convolutional layer in the middle of the network, it allows use to take in any sized image, as opposed to a fully connected layer that would require a specific set of input dimensions.

Intuitively, the encoder's job is to identify the important features in our image, keep those features in memory, remove the noise of other pixels, and decrease the width and height, while increasing layer depth.

For the first two layers, which comprise the encoder, and are in charge of determining the important features to extract from our input image, I chose strides=2, and the number of filters(adapted from ResNet and GoogLeNet) to be a power of 2: 2**6=64 for the first layer. This choice of strides=2 allows us to lose some dimensionality in height and width for the subsequent layer, and will help our memory and computational time. I will use this choice of strides=2 unless otherwise noted.

Recalling our function from lecture to determine the height/width of our subsequent layers: (N-F + 2*P)/S + 1

We can then calcualte what the size of our first layer will be:

layer1_height_width = (160-3 + 2*1)/2 +1 ; therefore, layer1 = 80x80x64 since we chose 64 filters(or kernels) of 3x3 filter dimension(which is a default setting).

This 3x3 dimension for the filter is very common, and my use of it here was also inspired by VGGNet-16. It should be mentioned that filter sizes of odd dimensions are common default values such as 3x3, 5x5, and 7x7; and are rarely seen larger.

For the second layer, I chose 2**7=128 filters of 3x3 size.

The encoder block harnesses the separable_conv2d_batchnorm(), which defaults to a kernel size of 3x3, and same padding(zeros at the edges). This will generate an output of K filter layers deep, with width and height of (N-F + 2*P)/S + 1.

def encoder_block(input_layer, filters, strides):

output_layer = separable_conv2d_batchnorm(input_layer, filters, strides)

return output_layer

The start of our model looks like this:

def fcn_model(inputs, num_classes):

# ENCODER

layer1 = encoder_block(inputs, 64, 2)

layer2 = encoder_block(layer1, 128, 2)

Now on to the middle portion of the network!

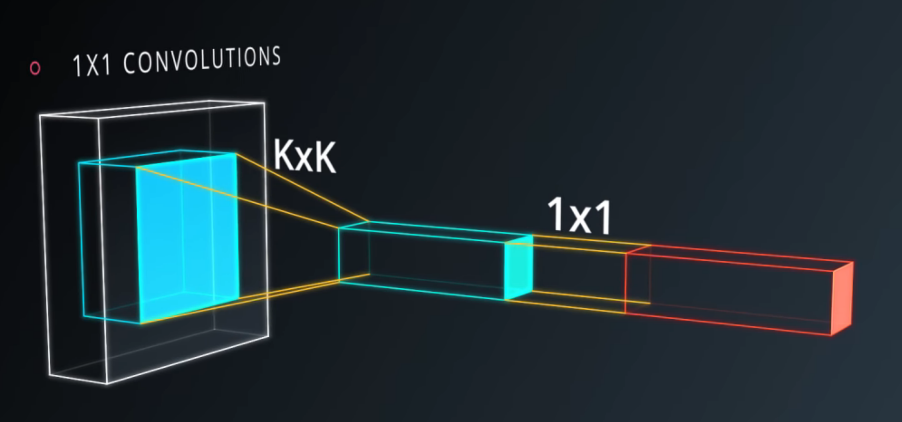

Between the Encoder Block and the Decoder block we opt to use a 1x1 convolutional layer.

This contrasts sharply with the conventional method for the task of Image classification. In Image Classification, our CNN would end with a fully connected 1x1 layer that would output a vector of c classes, each assigned a probability between 0-1 where the entire vector sums to 1(in the case of ImageNet classification, this would be 1,000 unit vector of class probabilities).

But since we're attempting to answer the question of WHERE, not just WHAT, we'll use a 1x1 convolutional layer for the task of semantic segmentation. This will allow us to assign individual pixels to one of the three classes.

Moving away from fully connected layers, and toward 1x1 convolutional layers provides us the following advantages:

- It makes our network more flexible by allowing different sized input images, instead of being fixed to one size

- It decreases dimensions, while preserving spatial information of the image, which allows us to output a segmented image

- It adds depth to our model and increases parameters at a fairly low computational price.

Our new 1x1 convolution looks like this:

I went all the way to 2**8=256 filters for the middle 1x1 convolutional layer, so we wouldn't compromise spatial data from our image.

The next portion of our fcn_model function is:

def fcn_model(inputs, num_classes):

# See encoder portion from above!

# 1x1 Convolution layer using conv2d_batchnorm()

layer3 = conv2d_batchnorm(layer2, 256, kernel_size=1, strides=1)

On to the next section of the model!

Upsampling is crucial in the second half of our FCN in order to transform the important features we learned from encoding into the final segmented image in the output. Bilinear Upsampling helps transform our downsampled image back into the resolution of our original input image.

Here's a good dipiction of how different types of upsampling works:

As I mentioned, we'll be repeatedly using Bilinear Upsampling in the Decoder Layer. We're provided an upsampling function that we'll use:

def bilinear_upsample(input_layer):

output_layer = BilinearUpSampling2D((2,2))(input_layer)

return output_layer

In addition to bilinear_upsample, we'll use concatenation with layers.concatenate, which will help us implement skip connections, as well as the separable_conv2d_batchnorm function. These functions will make up our decoder_block function:

def decoder_block(small_ip_layer, large_ip_layer, filters):

# Upsample the small input layer using the bilinear_upsample() function.

upsample = bilinear_upsample(small_ip_layer)

# Concatenate the upsampled and large input layers using layers.concatenate

concat_layer = layers.concatenate([upsample, large_ip_layer])

# Add separable convolution layers

temp_layer = separable_conv2d_batchnorm(concat_layer, filters)

output_layer = separable_conv2d_batchnorm(temp_layer, filters)

return output_layer

The choice for the decoder was simple, in that I simply scaled back up from the middle 1x1 convolutional layer to the final output image size. In this moment, the term deconvolution feels fitting, as it is what I had in mind while building the decoder(however, I know it is a contentious term).

The next portion of the fcn_model function is:

def fcn_model(inputs, num_classes):

# See Encoder and 1x1 convolutional sections from above!

# DECODER

layer4 = decoder_block(layer3, layer1, 128)

layer5 = decoder_block(layer4, inputs, 64)

We finally apply our favorite activation function, Softmax, to generate the probability predictions for each of the pixels.

return layers.Conv2D(num_classes, 1, activation='softmax', padding='same')(layer5)

This completes our fcn_model function to be...

def fcn_model(inputs, num_classes):

layer1 = encoder_block(inputs, 64, 2)

layer2 = encoder_block(layer1, 128, 2)

layer3 = conv2d_batchnorm(layer2, 256, kernel_size=1, strides=1)

layer4 = decoder_block(layer3, layer1, 128)

layer5 = decoder_block(layer4, inputs, 64)

return layers.Conv2D(num_classes, 1, activation='softmax', padding='same')(layer5)

This final layer will be the same height and width of the input image, and will be c-classes deep. In our example, we have 3 classes deep because we are aiming to segment our pixels into one of the three classes!

After trying a variety of values for num_epochs and having it set too high -- and therefore having training take multiple hours on AWS, I decided on the following training values:

learning_rate = 0.001

batch_size = 64

num_epochs = 50

steps_per_epoch = 65

validation_steps = 50

workers = 120

steps_per_epoch_check = 4132/batch_size

print(steps_per_epoch_check)

learning_rate: The learning rate(aka alpha) is what we multiply with the derivative of the loss function, and subtract it from its respective weight. It is what fraction of the weights will be adjusted between runs.

The learning_rate was reasonably straight forward to set. I initially started with 0.0005, but found that the error was not decreasing fast enough, and it would take a very long time to train the network at this pace. So I opted for a rate which we have seen a good amount in the lecture of 0.001.

If the learning rate is too high, the network may overcorrect repeatedly beyond what is necessary, and might not ever come close to converging. With too low of a learning rate, the network may never have the Loss decrease enough, or it will simply take too long. But usually when in doubt, keep the learning rate low, and train for a long time, over many epochs.

batch_size: The batch size is the number of training examples to include in a single iteration. I set this as 64. I could have also used 128 or 32, as long as I adjusted steps per epoch also(explained below).

num_epochs: An epoch is a single pass through all of the training data. The number of epochs sets how many times you would like the network to see each individual image. I first started with ~100 epochs, but soon adjusted down to 50 after seeing the Estimated Time Remaining for training.

steps_per_epoch: This is the number of batches we should go through in one epoch. In order to utilize the full training set, it is wise to make sure batch_size*steps_per_epoch = number of training examples In our case, this is 64*65=4160, so a few images are seen more than once by the network(we have 4132 images in the training data provided).

validation_steps: Similar to steps per epoch, this value is for the validation set. The number of batches to go through in one epoch. The default value provided worked fine.

workers: This is the number of processes we can start on the CPU/GPU. Since I'm training on AWS, I'll opt to use as many workers/processes as they'll provide.

steps_per_epoch_check: Is a verification parameter I created in order to set steps_per_epoch. In the Jupyter notebook provided to us, it mentioned a good heuristic for setting steps_per_epoch is by taking the number of training images, and dividing by the batch_size.

I determined steps_per_epoch by using steps_per_epoch_check = 4132/batch_size, where 4132 is the number of training images. This came out to 64.XX, so I opted for steps_per_epoch = 65.

After some tuning of parameters, starting long epochs, then stopping. My first epoch looked something like this:

After 10 epochs, the error was decreasing greatly, really flattening out:

With these parameters, anything beyond 50 epochs would be excessive and wasteful. Each epoch was running about 150-170s on average, which is much better than on my local MacBookPro of ~ 800 seconds per epoch.

For the first evaluation, with learning_rate=0.001 I stopped the script after 10 epochs with 200 steps(because this would have taken all day, and cost me a lot of $$$). The loss was down to 0.03, and the final_score came out as ~0.395. I was encouraged by this, so I continued training with more epochs.

Next, I adjusted the steps to 65, kept the learning_rate=0.001 and the number of epochs to 50 -- because this should yield decent accuracy, but not take all day. The final_score came out as ~0.43, Success!

First and foremost, adding data to train on would be a significant improvement. After we've added more images, it would be wise to increase the number of epochs, and potentially decrease the learning rate -- assuming we have a lot of time/money/computational resources. This would give the network more opportunity to learn.

It would be my assumption additional data and training time would allow the network to classify the target more accurately, by showing it more facets and features of our target, repeatedly.

It also might be a smart idea to make the network deeper. From the research proven with ResNet / GoogLeNet, adding more convolutions with skipped connections could prove to be a very good idea.

In order for this Deep Neural Network to be used to follow another target: such as a cat or a dog, it would just need to be trained on a new set of data. Also, the encoder and decoder layer dimensions may have to adjusted depending on the overall depth of the network.