Hacked together by David Liao and Zhan Xiong Chin

Tested on: AWS g2.2xlarge instance (Linux ip-172-31-53-81 4.4.0-53-generic #74-Ubuntu SMP Fri Dec 2 15:59:10 UTC 2016 x86_64 x86_64 x86_64 GNU/Linux, Nvidia GK104GL [GRID 520])

Just run make. Requires CUDA, OpenCV, and CImg.

The field of computer vision is the dual to computer graphics. In many cases, the unknowns that we are solving for in optical models are swapped around. For example, the graphics problem "given camera motion and lighting + scene conditions, generate a photorealistic image" has the counterpart vision problem "given photorealistic images and estimated lighting + scene conditions, calculate the camera motion".

In this project, we take on the challenge of recovering a background scene from an image with both a background scene and an occluding layer (e.g. fence, glass pane reflection, non-symmetric objects). The input to the algorithm is a series of images extracted from a camera that pans across a scene in planar motion. The inspiration and intuition driving the solution of this challenge involves leveraging parallax motion of the foreground and background images to separate a foreground and background layer. Given the data parallel property of the challenge (per-pixel calculation), this algorithm is a perfect target for GPU acceleration. While the main focus is emphasized on the performance gained by implementing the algorithm on the GPU (as opposed to the CPU), we will briefly go over the algorithm.

Let's briefly go over the algorithm to get an idea of what's going on under the hood.

Input: a sequence of images (we use 5) with the middle one being the "reference frame"

Assumptions:

- There needs to be a distinct occluding layer and background layer

- The majority of the background and foreground motion needs to be uniform

- Every background pixel is visible in at least one frame

Output: A background image without obstruction

- Edge detection

- Sparse flow

- Layer separation

- Dense flow interpolation

- Warp matrix generation + Image warping

- Background and foreground initial estimated separation

Here we describe how we implement each step in the pipeline.

We use Canny's edge detection algorithm that has the sub-pipeline as follows:

- Grayscale conversion

- Noise removal (smoothing)

- Gradient calculation

- Non-maximum edge suppression

- Hysteresis

Step 1 is an intensity average and steps 2 + 3 are convolutions using a Gaussian kernel and Sobel operators.

Step 4 takes the edge direction and inspects pixels on both sides of the edge (in the forward and reverse direction of the gradient) and if the pixel is not a "mountain", it will be suppressed. The end result is thinned edges that are pixel thick.

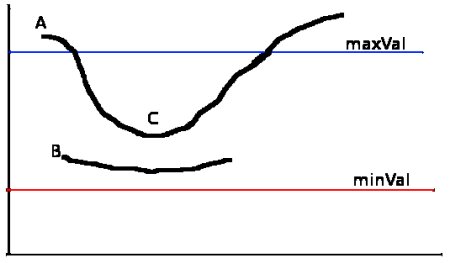

Step 5 is a technique to reduce noise in the edges when thresholding. When setting an intensity, threshold, it is possible that an edge dances around the boundaries of the threshold. The result is a noisy dotted edge that we don't want. Instead, we set a lower threshold and upper threshold where if an edge starts above the upper threshold but dips below the upper threshold while staying above the lower threshold, it will still be considered an edge. The below image borrowed from OpenCV docs gives a good idea of what this step does.

We then need to calculate how the image moves. The original paper defines a Markov Random Field over the edges, constraining pixels to match the location they flow to, as well as being similar to the flow of their neighboring pixels. We were not able to replicate this method, instead opting to use a more common optical flow algorithm, the Lucas-Kanade method, to approximate this. We made use of the OpenCV implementation for this step.

We run the Lucas-Kanade algorithm on the set of pixels that make up the edges. For each pixel, the Lucas-Kanade method assumes that the displacement of a small window (e.g. 21x21 pixels) around the window is constant between two frames, and sets up a system of linear equations on the spatial and temporal gradients of the window of pixels. Then, it uses least squares to solve this system of equations, with the result being the optical flow of the chosen pixel. While this is also ideal for GPU acceleration, as each pixel can be treated independently, we did not have time to write a kernel for this step. Also, the method no longer maintains similarity between adjacent pixels, so the flow may not be as continuous as the original paper's method.

To then figure out which edges are part of the occluding layer and which edges are part of the background layer, we use RANSAC to separate the vertices into two clusters.

For this, we make the assumption that both the occluding layer and the background layer are translated in the same way between two frames. This is also a simplification from the original paper's method, which estimates a homography rather than a simple translation.

Then, we fix a percentage P% of pixels that will be classified as part of the background layer. We pick a random initial starting vector v, then take the nearest P% of motion vectors to it and classify that as our background layer. Then, we take the mean of this newly computed background layer's optical flow, and treat this as our new vector v. Repeating the process a fixed number of iterations, we end up with a separation of pixels into background and foreground layer.

This did not always give stable results, so we augmented this with additional heuristics, such as separating based on the intensity of the pixels (e.g. when the occluding layer is a fence or racket, "whiter" areas tend to be part of the occluding layer, showing wall or sky)

After we figure out how the edges move and separate the, we interpolate sparse motion vectors of the background layer into a dense motion field. Basically we take the edge motion vectors and interpolate to figure out how every other pixel moves. There were two methods we used to calculate this. One was to do a K-nearest neighbors weighted interpolation, while the other was a naive average to generate an affine transformation matrix. As it turns out, the latter approximation works fine in the context of an initial estimate.

We take the background motion field from the last step and generate a warp matrix (basically inverting the motion matrix). Then apply it to all the non-reference images to warp them to the reference image. This has the effect of moving moving all the images in a way such that their backgrounds are stacked on top of each other. Their foreground, as a result, is the only moving layer.

After the last step, we've reduced the problem to a state where the camera perspective is static. We can then estimate a pixel for each layer based on this information.

Mean based estimation

If the occluding the layer is opaque, we can take the average of all the pixels at a location. If it is reflective, we can take the minimum (since reflection is additive light).

Alternatively, we can employ smarter techniques that take into account spatial coherence. In this case, we will select the pixel that has the most number of neightbors with a pixel intensity similar to it.

Spatial coherence based estimation

The quality of the image can be measured by an objective function defined over the foreground and background layers and motion fields, as well as the alpha mask between the two layers. Then, optimizing this objective function will (in principle) give a better image.

The original paper made use of an objective function that penalizes the following terms:

- Differences between the original image and the combination of the estimated background and foreground

- Noisy alpha mask

- Noisy background/foreground images

- High gradients on the same pixel of the background and foreground image (i.e. highly detailed of the image probably only belong to one layer rather than a mix of both)

- Noisy motion fields

They optimized this using iteratively reweighted least squares, using the pyramid method to start from a coarse image and optimize on successively finer ones.

For our code, we made use of the same objective function, but we performed a naive gradient descent to optimize the objective function. Tweaking the parameters of the optimization, we sometimes were able to obtain slightly better results, but in general, we did not find a significant improvement in image quality, possibly due to the slow convergence of our naive gradient descent approach.

The pipeline benchmarked exclusively for the individual kernel invocations. The overhead costs were excluded in this analysis as they are not useful/relevant. The input used was img/hanoiX.png where X is replaced by the image number. Please look at the entire recorded data set here. Note the tabs at the bottom!

Since the pipeline is sequential, performance bottlenecks are distributed across each pipeline step and can be targets for future improvement. The most notable bottleneck is the RANSAC algorithm. Since it is an iterative model, tweaking iteration parameters would speed it up at the cost of accuracy. At its current benchmarked state, it is running ~50 iterations. So each iteration runs at about ~2 ms.

Reflection removal as well. Top left: original image, top right: separation, bottom left: without gradient descent, bottom right: with gradient descent

Removing the spokes of a bike wheel from Harrison College House.

When canny edge detection goes wrong...

A bug in the pipeline propagates and magnifies in the pipeline downstream.

We want to give a big thanks to Patrick Cozzi for teaching the CIS 565 course as well as Benedict Brown for giving us general CV tips.