-

Notifications

You must be signed in to change notification settings - Fork 53

prelecture_13_forces_and_torques_on_currents

Kurt Robert Rudolph edited this page Jul 1, 2012

·

11 revisions

- Continue study of magnetism by studying the forces and torques

exerted on currents carrying wires and magnetic fields.

- First, calculate the forces on strait and curved wires in constant magnetic fields

- Next, calculate the torque on a closed loop of current in a magnetic field.

- Next, introduce the concept of the dipole moment.

- Last, we use this dipole moment to define the potential energy that is associated with a current loop located in a region of space that contains a magnetic field.

- Last time, we learned charges moving in a uniform magnetic field experience a force that is proportional to the charge, magnetic field, and component of the velocity perpendicular to the magnetic field. The direction is perpendicular to both the magnetic field and the velocity.

- Now, we discuss what happens when a current carrying wire is placed in a region of space

that contains a magnetic field.

- Current is composed of charges in motion we expect that there will be some sort of force exerted on the wire.

- Using the right hand rule we determine the force to be in the upward direction

- Now calculate the magnitude of this force.

- [\vec F = I \vec L \times \vec B]

- [\vec F = \sum\limits_{i}{ \vec F_i} = q \sum\limits_{i}{ \vec v_i \times \vec B]

- [= q (N \vec v_{avg}) \times \vec B ]

- [N = n A L] where [n] is the number of charges carriers per volume in the wire and [A L] is the volume of the wire.

- [= q n A L \vec v_{avg} \times \vec B]

- [I = n A q v_{avg}]

- The net force is vector sum of the force acting on each of the individual charges carried through the wire.

- Since the charges are constrained within the wire it is also the net force on the wire.

What units result when a velocity [v] is multiplied by an area [A]?

- Volume per second

- The units of velocity are [\frac{ m}{ s}] and the units of area are [m^2], and when we multiply these together we get [\frac{ m^3}{ s}] which is volume per second.

- A simple and useful way to picture this is to think of water flowing in a garden hose. If the speed of the water is known, [v = 10 \frac{ m}{ s} = 1,000 \frac{ cm}{ s}] for example, and the cross-sectional area of the hose is also known, [A = 10 cm^2] for example, then the volume of water that travels past any point of the hose is every second is [v A = 10,000 \frac{ cm^3}{ s} = 10 \frac{ liters}{ s}]. In other words, if we know the velocity of the water and the area of the hose we can easily figure out the volume of water transported by the hose per unit time. If we multiply this by the density of water, i.e. [10 \frac{ liters}{ s} \frac{ kg}{ liter} = 10 \frac{ kg}{ s}], then we immediately discover how much mass is moving past a point in the hose the hose per unit time.

- This has an exact analogy with current in a wire. Think of the wire as the hose and the current flowing in the wire as the water. The average velocity of the charges [v_{avg}] times the area of the wire [A] tells us the volume of the charge carriers that moves through the wire per unit time. If we multiply this by the number density of the charge carriers n we find the number of charge carriers per unit time flowing in the wire, and if we multiply this by the charge carried by each one [q] we find the charge per unit time flowing in the wire.

- In other words, the current in the wire [I] is equal to the product [q n A v_{avg}].

- Consider the wire to be made up of sufficiently small wire segments

[s] and look at the vector sum of the force on these segments to get

the net force on the wire.

- [\vec F_{wire} = \sum \vec F_{i} = \sum\limits_{i}{ I d \vec s_i \times \vec B} = \int{ I d \vec s \times \vec B}]

- [= \int I d \vec s_{|} \times \vec B + \int I d \vec s_{\perp} \times \vec B]

- [= \int I d \vec s_{\perp} \times \vec B]

- since [\int I d \vec s_{|} \times \vec B = 0]

- [= I B \int d s_{\perp}]

- since [I] and [B] are constant

- [= I B (L_{\perp}) = I \vec L \times \vec B]

- The force on the wire does not depend on the exact shape of the wire but rather only the distance between the perpendicular components of the wire.

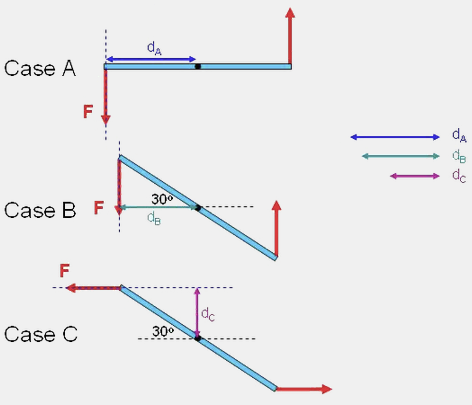

The above illustration shows three different current segments [A], [B] and [C] in a uniform magnetic field. The magnitude of the current in each segment is the same. If [F_A], [F_B], and [F_C] are the magnitudes of the magnetic forces on each segment, rank these forces from largest to smallest.

- [F_B > F_A > F_C]

- If the currents are the same then the force depends on only on the distance between the ends of the segment as measured along the direction perpendicular to the magnetic field. This is zero for [C] and is bigger for [B] than it is for [A].

- [\vec F_{ClosedLoop} = 0]

- [\vec F = I \vec L \times B]

- [\vec F_{12} + \vec F_{34} = 0]

- [\vec F_{23} + \vec F_{41} = 0]

- While net force on a loop is zero, torque is usually not zero

- [\tau_{loop} = I A B \sin \theta]

- Recall that the torque on an object is equal to the cross

product of that force and the distance to where the force is applied.

- [\vec \tau = \vec r \times \vec F]

- Magnitude [tau = r F \sin \theta]

- Consider the side view of the closed loop rotated on it's axis

- [\tau_{12} = \frac{ h}{ 2} F_{12} \sin \theta]

- [\tau_{34} = \frac{ h}{ 2} F_{34} \sin \theta]

- both [\tau_{34}] and [\tau_{12}] tend to rotate the loop clockwise

- [\tau_{total} = \frac{ h}{ 2} (F_{12} + F_{34}) \sin \theta]

- [= \frac{ h}{ 2} (2 I w B) \sin \theta] * since [F_{12} = F_{34} = I w B]

- hence [\tau_{loop} = I w h B \sin \theta] where [w] is the width and [h] is the height and in turn [w h] is the area of the loop.

- therefore we are able to generalize this for any loop [\tau_{loop} = I A B \sin \theta]

Three cases involving identical forces acting on identical sticks are shown at the right. Compare the magnitudes of torques about an axis through the center of the sticks.

- [\text{Torque}( A) > \text{Torque}( B) > \text{Torque}( C)]

- The magnitude of the torque due to a force [F] is the product of the magnitude of the force and the lever arm, defined as the perpendicular distance from the rotation axis to the line defined by the force. Since the forces are all the same in the cases shown here, the relative lengths of the lever arms will define the relative magnitudes of the torques:

- Previously, looked at torque within a loop which is dependent of three things

- Current in the loop

- Area defined by the loop

- Orientation of the loop with respect the magnetic field

- Now, combine all three of the components which define the torque

into one new quantity the magnetic dipole of a loop.

- Area Vector

- [|\vec A|] is the area of the loop

- direction of [A] is perpendicular to the plane defined by the loop.

- Define the positive direction of [A] using the direction of the current

- Curl fingers in direction of [I]

- Thumb points in direction of [\vec A]

- Magnetic Dipole momoent

- [\vec \mu = I \vec A]

- or for a soy a coil containing [N] turns [\vec \mu = N I \vec A]

- Torque on a loop

- [\vec \tau = \vec \mu \times \vec B]

- Area Vector

- [U(\theta) = -\vec \mu \cdot \vec B]

- we just saw that the torque on a current loop in a magnetic field depends on the orientation of the loop magnetic moment vector with respect to the magnetic field.

- recall [W = \int \tau d \theta = \int\limits_{90^{\circ}}^{0^{\circ}}{ (-\mu B \sin \theta) d \theta = \mu B}]

- We can define work between any two starting and stopping points as [W = \int\limits_{\theta_1}^{\theta_2}{ (- \mu B \sin \theta) d \theta}]

- looking at potential energy

- [\Delta U = -W_{\text{by B field}} = \int\limits_{\theta_1}^{\theta_2}{ (- \mu B \sin \theta) d \theta}]

- [U( \theta) = \int\limits_{90^{\circ}}^{\theta}{ (- \mu B \sin \theta) d \theta} = -\mu B (\cos \theta - \cos 90^{\circ}) = -\mu B \cos \theta = \vec \mu \cdot \vec B]

- First we investigated the force on a current carrying wire by a magnetic field

- [\vec F = I \vec L \times \vec B]

- We then determined that the same expression holds

for a wire if we define [L] between it's two ends.

- A special case is the loop

- [\vec F_{ClosedLoop} = 0]

- Magnetic Dipole Moment

- [\vec \mu = N I \vec A]

- Torque on a loop

- [\vec \tau = \vec \mu \times \vec B]

- Potential energy

- [\Delta U = - W_{\text{by B field}}]

- [U( \theta) = -\vec \mu \cdot \vec B]